Deep Learning

Teaching for Deep Learning requires specific skills we could all learn and use.

Some particular dynamic instructional initiatives capturing educators' attention these days are actually powerful items mined from the knowledge base we already have. Time to bring them to scale!

Thanks to many like Tony Wagner (2014, 2020), the constellation of Student Agency and Ownership, Meaning, Collaborative Social Skills and Structures, and Creativity have been lifted up and unified in certain models of instruction to be found in islands of progress all over the country. These models go under different names, but “deeper learning” is the au courant term we hear most often. Others are:

- Project based Learning

- Personalized Learning

- Active Learning

- Student Centered Learning

- Whole school models like High Tech High

- Examples in Ted Dintersmith's What Schools Could Be

- Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine’s Deep Learning (2019)

Every one of these has in common the development of Student Agency (choice, voice, initiative) and Meaning. Students see how the tasks and learning they are doing connects to their future life and to meaningful purposes. These are generic elements of powerful teaching and learning that we can develop if we choose in any classroom at any level.

The first part of this article uncovers the long history of these ideas for deeper learning. The second part profiles the teacher skills it takes to offer deeper learning to students.

Forbearers of Deeper Learning

Creating student experiences that have these features is supported by 100 years of validated research from distinguished scholars. Wagner (2014, 2020 ) made important contributions to our understanding of what engaged learning is for 21st century learners. Pam Grossman et al (2021) breaks out these same elements in analyzing Project Based Learning and includes the skills of teaching students how to collaborate and a set of other core practices characteristic of high-expertise teaching, like providing students with useful feedback and tracking students' progress.

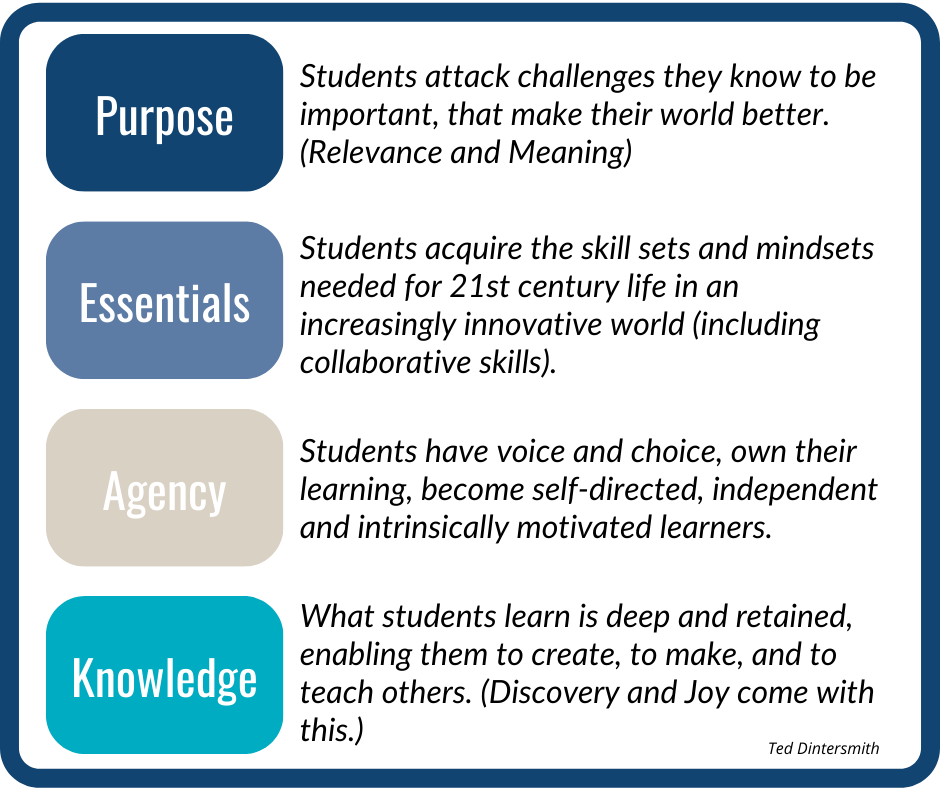

In What School Could Be, Ted Dintersmith (2018) did a year-long tour of schools all over the U.S.A. to find the best in American education. He found that the best provide students with Purpose, Essentials, Agency and Knowledge.

Purpose -- Students attack challenges they know to be important, that make their world better. (Relevance and Meaning).

Essentials -- Students acquire the skill sets and mindsets needed for 21st century life in an increasingly innovative world (including collaborative skills).

Agency -- Students have voice and choice, own their learning, become self-directed, independent and intrinsically motivated learners.

Knowledge -- What students learn is deep and retained, enabling them to create, to make, and to teach others. (Discovery and Joy come with this.)

Dintersmith found teachers and sometimes (but rarely) entire schools that developed these conditions. A century of wisdom writing and passionate advocacy has always struck these same themes. Ironically, Dintersmith’s findings mirror what progressive educators have been advocating and building into experimental schools for well over a century.

Similar findings come from Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine in their 2019 book, Deep Learning (2019).

Before WWII John Dewey pioneered rethinking the egg crate school structure we had imported from Germany in 1893 and its supposed objectives of teaching basic skills, inculcating compliance and sorting students. Dewey advocated active learning, student agency and social interaction.

Before him had been Maria Montessori. After him came a succession of innovators who translated their theories of good education into functioning models. Paulo Freire advocated a critical pedagogy of agency and meaning aiming at social justice. A.S. Neill founded a school (Summerhill) based on freedom of choice and student agency. John Holt bought similar ideas of freedom and student agency to his own teaching and writing. William Glasser brought social interaction, goal setting (a form of agency) and social problem-solving into the daily rhythm of class life. High Tech High in San Diego embodies instruction right now that infuses into classroom life meaning and relevance as well as student agency and the acquisition of planning and technical skills. Project-Based Learning in the current era carries forward the commitment to relevance and student agency. Michael Fullan's international alliance to pursue "Deep Learning" also embodies Dintersmith's findings.

Almost 30 years ago as Martin Haberman was developing his work on "Star Teachers", he recounted examples of student experiences such people create. Note that they all embed student agency and meaning. Students are:

- engaged with issues they regard as important/vital;

- involved with explanations of human differences;

- being helped to see major concepts, big ideas, and general principles and are not merely engaged in the pursuit of isolated facts;

- involved in planning what they will be doing;

- involved with applying ideals such as fairness, equity, or justice to their world;

- directly involved in a real-life experience;

- actively involved in heterogeneous groups,

- asked to think about an idea in a way that questions common sense or a widely accepted assumption, that relates new ideas to ones learned previously, or that applies an idea to the problems of living;

- involved in redoing, polishing, or perfecting their work;

- involved with the technology of information access;

- involved in reflecting on their own lives and how they have come to believe and feel as they do

- Haberman 1991

The Science of Learning and the Skills to Use It – facts, not ideology

Building "student agency" into classroom life is validated by the science of learning (Dealing-Hammond et al 2021) and calls forth a constellation of generic skills for teachers to develop in students. They are embedded in the routines and procedures of daily classroom life. The skills for students doing these operations are taught to them and practiced. These skills include supporting students to:

- make choices,

- be in charge of keeping records of how they are doing,

- set goals

- make plans of action,

- prepare student-led parent conferences,

- do self-evaluation about the implementation of plans they make.

- work on tasks relevant to real world issues that can be local or universal.

In fully developed classrooms and schools, students are working on tasks that are meaningful to them. They are seeking to make something and/or impact how something is done outside their classroom in the "real world" that can make a difference.

Developing student agency requires teachers to understand the structures and routines of offering students choices. It also calls for interactive verbal skills teachers use to induce higher-level student thinking through robust student conversations. The teacher skills for doing all these things are known and have names (Saphier 2018) and specifications for successful implementation. It's just that they are absent from most teacher's repertoires because teachers have no preparation in how to employ them or any accountability for using them.

The skills above are essential ingredients in any comprehensive map of high-expertise teaching. And like everything else in this knowledge base, they are research based. Agency and Meaning have long been known to be powerful variables in student learning. Any of us can bring these skills alive in our classroom now by undertaking the professional learning it takes to do so. It doesn’t require a redesigned school to make these qualities integral to students’ experience in one class.

I am emphasizing the concept of "Skills" here because research validated skills are teachable and learnable. They are not ideological positions. Learning them can be designed into the personnel pipeline if one takes a long-term and systemic approach. That is what we have to do. The motivation to learn the skills may be based on certain beliefs, but abstractions like "make learning experiences meaningful" are not enough. We need to know what to do in daily practice to make the rosy injunctions come true.

The authors above and their models have had profound impact on the students who experienced them, yet failed to influence the practice of broad swaths of educators (with the possible exception of today's steadily growing interest in Project Based Learning). My argument is that these movements do not represent ideologies, though the debates over the decades certainly have been framed as ideological. The movements embody fundamental elements of successful schools long established by research (Darling-Hammond et al 2021). What may be ideological is the face-off between wanting school to be a mechanism of control and socialization for compliance vs. wanting school to be a place of developing human capacity to think at high levels, identify and solve problems, and operate successfully with others.

It is not ideological to operate from a perception that agency, understood as a person's ownership and commitment to accomplish something, mobilizes energy and resourcefulness that increases the chance of accomplishing the goal. That is established fact. If that person knows how to set reasonable goals and make systematic plans of action to reach a goal, all the more chance of success. Setting up a class to be that kind of place is a skill-based endeavor.

Some readers may push back on this distinction between ideology and skill-based teaching. They will argue that what I and my colleagues choose to include in the encyclopedia of skills for High-Expertise Teaching are really value positions ("Students should be empowered to own their learning.") I argue that student empowerment is known for a fact to make for deeper and more durable learning. It's the same kind of argument that points to the significance and the impact on learning of personal relationships between students and teachers - relationships of regard and respect. Knowing how to generate student agency and build personal relationships are skills. Values won't tell you what to do to actualize them.

If it is ideological to want schools to use scientific knowledge about student learning to improve it, then I'll say "OK, no point in arguing about that. Let's get on with it!"

References

Darling-Hammond, Linda, Pamela Cantor, Laura E. Hernández, Abby Schachner, Sara Plasencia , Christina Theokas, Elizabeth Tijerina. Design Principles for Schools. Learning Policy Institute. Palo Alto CA: 2021

Dintersmith, Ted. What Schools Could Be. Princeton University Press. Princeton, N.J.: 2018

Glasser, William. Schools Without Failure. Harper and Row. New York: 1975

Grossman, Pam, Zachary Herrmann, Christopher G Pupnik Dean, Saran Schneider Kavanagh. Core Practices in Project Based Learning. Harvard University Press. Cambridge MA: 2021

Haberman, Martin. Phi Delta Kappan, v73 n4 p290-94 Dec 1991

Mehta, Jal and Sarah Fine. In Search of Deep Learning. Harvard University Press. Cambridge MA: 2019

Saphier et al, The Skillful Teacher. Principles of Learning Chapter: Meaning; Relevance; Goal Setting. Clarity skills of Making Students Thinking visible; Criteria for success; Student self-evaluation. Research for Better Teaching, Acton MA: 2018

Wagner, Tony. Learning by Heart. Penguin Random House. New York: 2020

Wagner, Tony. The Global Achievement Gap. Basic Books. New York: 2014