Five Ways to Make Feedback Matter

After a year of pandemic living, superintendents, central office leaders, and principals continue to lead under ever-changing conditions. Problems once easily addressed seem larger. Everything takes twice as long. Conversations are rushed when jumping between zoom meetings. Follow-up is random. A colleague sums up the strain, "I'm trying to keep all the balls up in the air and not doing a good job of helping those around me who drop them."

I'm trying to keep all the balls up in the air and not doing a good job of helping those around me who drop them. |

Yet, we know that an important part of our role is being present - engaging and supporting our colleagues in conversations about practice. Pre-pandemic surveys (Gallup Poll, 2019) found only 26% of employees believed feedback was helpful. Yet, an astounding 92% shared that even one piece of constructive feedback delivered appropriately, could make a difference. With remote learning, we miss the in-person feedback opportunities that nurture us as leaders: popping into a classroom to validate a first-year teacher's efforts, circling back to the team dissecting student writing, and unpacking the worries of a brand-new administrator who is having second thoughts about his career path. Though we may feel we have fallen short in supporting others during these last challenging months, as we look forward to the return of in-person learning, we must return our focus to providing feedback to those we supervise because we know how important it is.

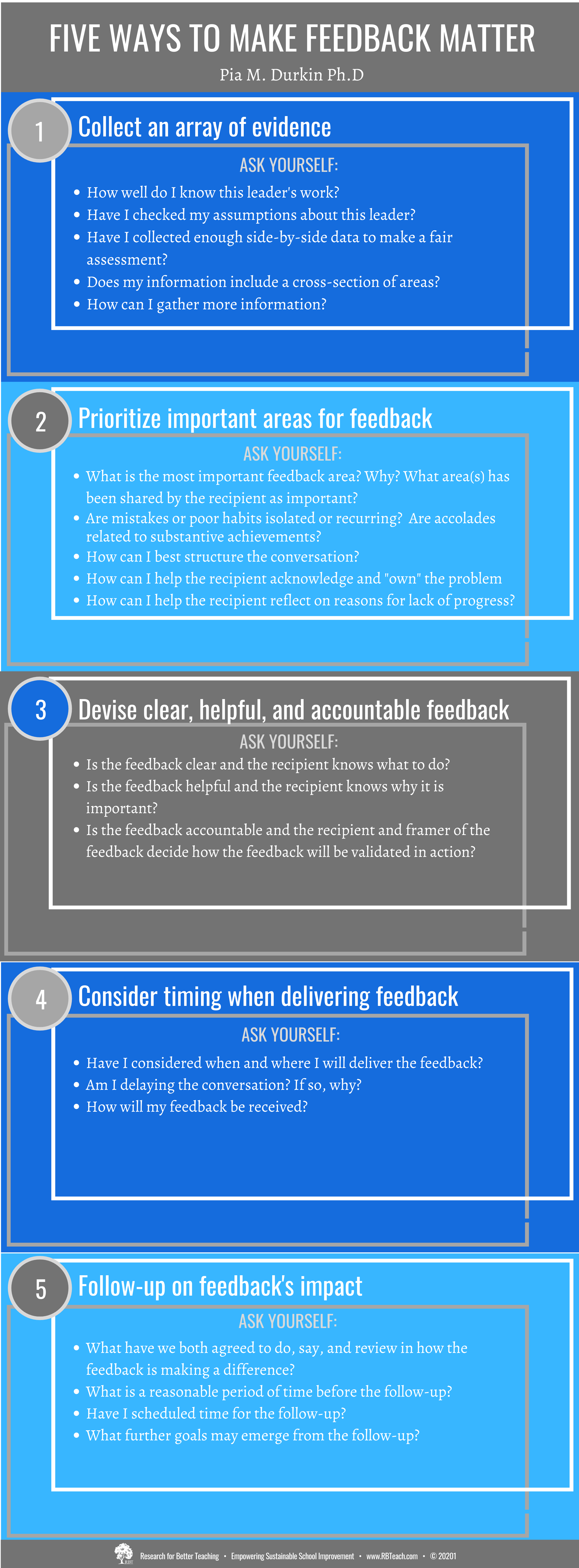

Five practical strategies demonstrate how committing time and effort to focus on feedback areas (will) and attentively constructing the content and the logistics for delivering it (skill) serve as powerful tools for changing performance:

1. Collect an array of evidence.

Feedback is based on data. Frequent and varied interactions between the framer and recipient of the feedback ensures credibility and trust. When a supervisor is seen only in group meetings, heard mostly through emails, and visits schools/ departments irregularly, feedback can be discounted and difficult to accept. Even positive feedback seems disingenuous. As one principal shares, "I hear plenty of platitudes, but I still don't know how to get better at my job to move my school. My supervisor just doesn't know my work." Feedback, built on relationships, begins with noting what, how, and where to collect performance information.

2. Prioritize important areas for feedback.

When planning feedback, stick to the Goldilocks Rule - not too much, not too little, just enough. Less is more in prioritizing high-impact areas. When reviewing both mistakes and kudos, discernment matters. Everyone makes mistakes but if the same mistake keeps recurring, feedback is needed. On the flip side, a well-praised leader's work may warrant a deeper look below the surface, such as reviewing student subgroup results. Looking "under the hood" of performance helps outline priorities, focus on how the recipient can best "hear" the feedback, and come to consensus why it is important.

3. Devise clear, helpful, and accountable feedback.

When feedback is not clear on what to do to improve, we do recipients no favors. When feedback is not helpful to leaders' real challenges, we abdicate our responsibility to support and stretch them. When we are not accountable for the feedback we deliver, we limit its value and conduct merely a compliance exercise. We lift our feedback by making it clear in its impact and next steps, helpful in addressing the issue(s), and accountable by committing to review it in action.

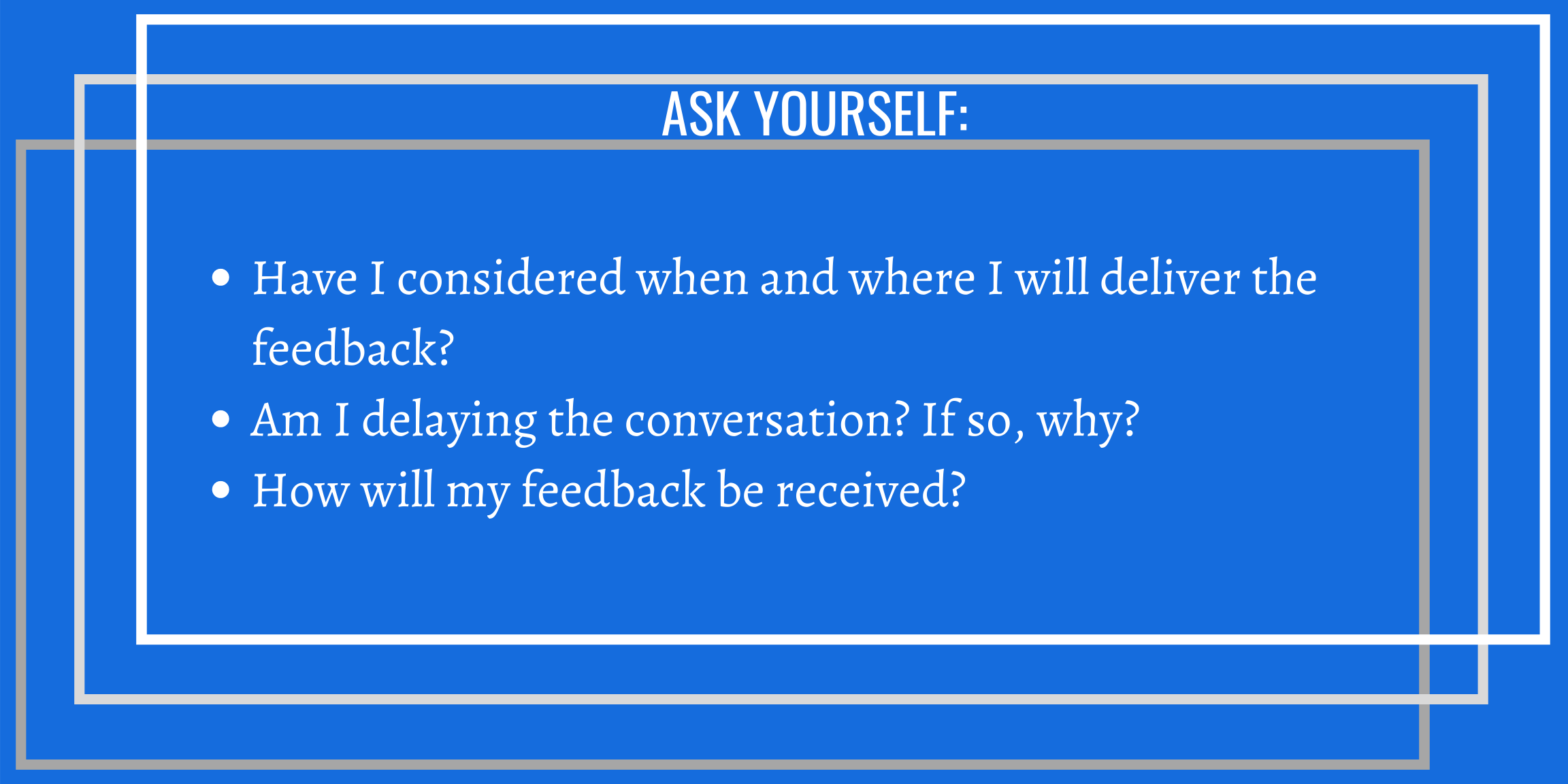

4. Consider timing when delivering feedback.

Deciding when to deliver feedback is as important as deriving its content. Be aware of the "avoidance virus" and the urge to procrastinate. With difficult feedback, waiting too long can exacerbate a situation resulting in more time spent on the original problem. When reacting too quickly, feedback may be haphazard with emotions getting the better of us. Checks and balances can help. Note if a delay may be for pragmatic reasons (for example, an individual may be struggling with certain circumstances) or if the delay is related to your own emotional reluctance. With the latter, acknowledge those feelings, prepare for possible consequences, and move forward. Positive feedback also requires timely vigilance. Hard workers who receive little to no feedback, feel less valued and may choose to work elsewhere.

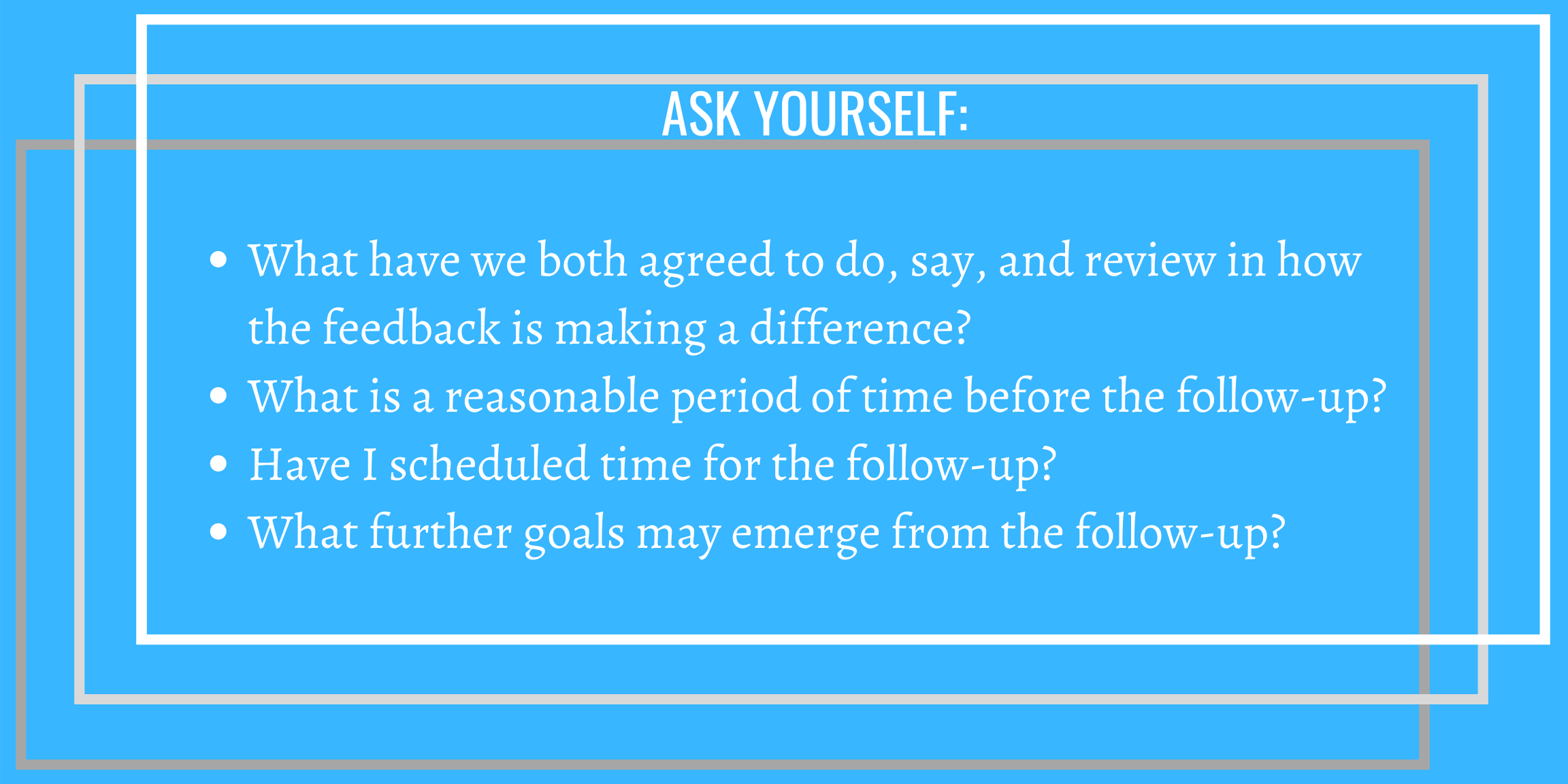

5. Follow-up on feedback's impact.

When you provide feedback, you enter into a contract to make sure it has impact. Both the framer and the recipient are accountable for follow-up to happen, even though best intentions may go awry. The old adage holds true: do what you say and say what you'll do. Timely follow-up sets the stage for future goal setting and shapes continuous learning.

Though we recently may not have given enough of the right feedback, ignored those who needed feedback, or rarely followed-up on the feedback we did give, it is never too late to change our practice. While we look towards the end of the school year and the hopeful return to in-person learning, we need to begin implementing strategies to ensure we are providing thoughtful feedback to those we supervise.

When feedback is planned and delivered well, the supervisory relationship deepens and affirms the reasons why we originally became leaders - to provide others the chance to become better at what they do, so they can do the same for the adults and children they serve.

Download the Five Ways to Make Feedback Matter questions- for easy reference.