The Years of Magical Thinking

The world of fantasy novels is populated with wizards, kings, nobles, villains, monsters and magicians. In the end, when there is a happy ending, it is the heroes and the magicians who often join forces to save the kingdom.

In 50 years of education reform we have had all these same characters: our heroes and villains, our nobles and our magicians. It would be an amusing game to compile lists and compare why we put our characters in each category. My contention in this article is that an over-reliance on magicians and magical thinking has been a main reason why, after this long history, serious concerns about our education system, woeful international comparisons, or the continuing achievement gap persist unabated.

We have ignored teaching expertise.

“Expertise” is a bigger concept than “skill”. Skills in teaching, of course, are vital—skills like knowing how to do Modeling Thinking Aloud, how to construct an objective in mastery language and make sure students understand it. Expertise, though, includes the judgment to know when to use a skill and in what context. Experts can match the use of a skill to the student, the situation or the curriculum. But expertise in teaching also includes additional radically different domains: e.g., building relationships of regard and respect, doing content analysis for relationship of concepts and for potential confusions, motivating discouraged students, creating culturally relevant lessons for the students in front of us, getting students to believe in themselves, converting disruptive behavior into cooperation (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Expertise also means knowing how to analyze student errors and plan successful re-teaching to those who didn't get it the first time around. It means teaching students how to be good at being students! And it means making these far ranging skills widely distributed and readily available to our most marginalized students.

In the U.S. we have put our chips in off-center reforms for decades. In the 70s and 80s we thought better curriculum packages would be the thing (whole language approaches, science kits…). In the 90s, it was the creation of new structures (small high schools, site based decision-making councils, freshman advisories...). In the 2000s, it was standards and accountability. In the 2010s it was using data (PLCs, interim assessments, data teams.) In the current decade it has been personalized learning, deep learning, and project based learning. Each of these initiatives contributed valuable and often necessary supports for having schools provide what all children, need. Who could argue with the focus on the achievement gap that the standards movement brought into focus, or the case for connecting learning to meaningful issues in students’ lives that deep learning brings to the table. None of these, however, went to the heart of the matter.

Therefore, vastly uneven student achievement has persisted, and the achievement gap for children living in poverty and children of color has continued with barely a dent.

I’ve spent 50 years as a practitioner, 40 working with school districts on the inside as a consultant and 10 as a teacher and administrator. These decades have convinced me and my colleagues that if we could put teaching expertise, broadly defined and understood, at the center of education reform and pursue its development systemically, we could make all the potential of other reforms bear fruit. And without that, we will not be able to get to scale with any of the others. It takes a solid foundation of teaching expertise to implement any progressive improvement approach; and we deny that foundation to our career professionals. This fact is shocking, amazing, and tragic. It is shocking to see how threadbare our personnel pipeline for creating high-expertise practitioners is. It is amazing that with all the knowledge about successful teaching that has accumulated since the 60’s, our policy makers at every level (local board, state, federal) have failed to move to make it accessible to our educators and required to teach children. It is tragic for our children, especially our marginalized children, that we cannot guarantee they will all receive a high-expertise teacher.

There is no denying the pernicious effects of poverty. Yet individual schools defy terrible neighborhood and family conditions every year and achieve results for children that might otherwise be thought impossible. The heart of the matter is high-expertise teaching, conceived comprehensively in all its range and complexity. Define it as anything a person does that influences the probability of intended learning, and leadership for creating an adult environment where it constantly grows.

Teaching expertise dwarfs other variables among the items we control in schools (Sanders and Rivers 1996.) And it has stunning and persistent results in school after school where it is developed. It has been the missing element of school reform. Sadly, the personnel pipeline into teaching that could produce these results widely is a shadow of what it could be; it is profoundly dysfunctional, disconnected, and disregarded (Saphier 2010.)

Sanders and Rivers (1996)

To be clear, this personnel problem is more properly deemed an expertise problem. To teach really well takes a level of expertise on a par with that required for high-level performance in architecture, law, or engineering. Those professions have a complex and codified knowledge base that practitioners take many years to acquire through education, apprenticeships and mentoring on teams. We may get by without using the full range of extant knowledge and skill about teaching and learning if our children come from high expectations families and affluence. These children may have the experience of being read to since the age of one, the experience of travel, museums, music lessons, sports teams with coaching, lively dinner conversations, family picnics, national parks, camping. But high-expertise teaching is required for many of our children living in poverty, and if we could generate enough of it, we wouldn't have the intractable achievement gap we do today.

This gap exists particularly for children who are behind and discouraged and don't believe in themselves, for children who have experienced trauma, for children who have concluded that they can't do well in school, and for children of color denied opportunities by racism. Most of our tragically large population of children with gaps of opportunity (1) lag significantly behind more fortunate peers, but they can catch up if they have expert teaching consistently. But most of them don’t get it, and the learning deficit accumulates annually until many children are three grade levels behind by 9th grade.

This may seem like a bizarre claim for readers who believe the damage of poverty and racism is permanent and irredeemable. I would not argue the point that children who come to school malnourished are not ready to learn; nor that the effects of trauma are not formidable. But again and again we see that for all but the most damaged children, proficiency is possible for children of poverty (see every year's Education Trust list of such schools.)

The Big Rocks of High-Expertise Teaching summarizes the highest-leverage elements of high-expertise teaching. There is no question about these. They all show up every ten years when distinguished researchers do meta-analyses of the research on teaching effectiveness. (Bellon and Bellon 1992, Marzano 2007, Hattie 2012.) (2) But they are far more than any teacher education program could impart to candidates becoming beginning teachers. Beginning teachers are competent novices at best. Furthermore, one could go into 100 classrooms at random in any school district and see few if any of these high-impact skills at work. That is because there is no organized system for acquiring them, no state policy that they should be acquired, and no infrastructure to teach them to our teacher workforce.

Note that of the items in The Big Rocks of High-Expertise Teaching, three of the ten call for active teacher beliefs and commitments (numbers 6, 7, and 8.) High-expertise teaching calls for more than just technical skills.

Another surprising benefit for a focus on High-Expertise teaching is in Special Education. If we have too many children in Special Education and upward trending Sped budgets, we could reduce that population significantly with more high-expertise teaching across our entire teacher corps.

None of this is to blame the scores of dedicated and professional teachers we have. The issue is access and accountability for a huge and multifaceted knowledge base. What's missing is holding policy makers responsible for creating conditions that would deliver this expertise.

Those who argue for higher salaries and better working conditions to attract young men and women into the profession are not off base. But the irony is that our present teacher corps, loaded with idealistic service-oriented people, has the personal capacity to achieve high-expertise practice right now. We don't need different people; we don't need better people. We need a highly articulated personnel pipeline for teachers, and surely also for leaders, that achieves the level of expertise of which our people are capable.

I say also "for leaders" because individual building leaders either create or don't create workplaces where constant learning about high-expertise teaching takes place daily in the way business is conducted. They build a strong Adult Professional Culture of constant learning and non-defensive examination of practice in relation to student results. But more on that later.

Note that the creation of teacher evaluation rubrics in the 2000s (Danielson, Marzano, Marshall) served the purpose of profiling the range of skills necessary for fully effective practice. These rubrics did not do much, however, to show in accessible detail what a person would say or do to validly attain high ratings. The boxes in these rubrics contain abstractions (e.g., "Communicates high expectations to all students").

We actually do know what that "box" would look and sound like in action (Saphier 2017), but it's quite a bit more complex than one can ever get by just reading these omnipresent rubrics. And instructional leaders (especially principals) usually have little skill or training in how to pick up the behaviors that would be evidence of a rating on this rubric item or how to support a teacher toward reaching proficiency in a given skill.. (Fink 2017.)

Here is the take-off point for developing a cohesive personnel pipeline: we do know at a drill-down detail level what high-expertise teaching looks and sounds like (Saphier, Haley-Speca and Gower 2018). We know of all the skills that comprise high-expertise teaching which ones have the most impact on student learning (Hattie 2012). And we know what leaders do to bring these alive for their teachers (Bryk et al. 2010). We also know that this knowledge and skill base is far larger and more complex than our voting public or policy community realizes, and is perennially absent from the practice of huge numbers of our teachers. (see consistent studies from Goodlad 1984 to Pianta 2007.) (3)

What we need to create, which we do not have, is a personnel pipeline that develops high-expertise teaching steadily and comprehensively over a person's teaching career. This kind of a pipeline does exist in Japan and Finland, and shows up in daily adult interactions (Hiebert and Stigler 2017.) It is deliberate there, it is national policy there, it is budgeted there, it is a cultural expectation there, and it is publicly supported there.

There are seven internal processes schools control that could function as an articulated personnel infrastructure: hiring practices, induction programs, teacher evaluation systems, structured professional growth systems, protocols for time use by teams of teachers who share content, and the job and role definition of instructional coaches. They could comprise a deliberate, integrated personnel pipeline for high-expertise teaching (Saphier 2005), because each of these processes influences (or could influence) what a teacher knows and can do. And nothing is more influential in student achievement than high-expertise teaching, (Mendro et al 2000; Nye et al. 2004)

Better pre-service teacher education is certainly needed. Some outstanding programs already exist in this country (though far too few.) But the bulk of high-expertise teaching will be learned after graduation as it is in other professions!

Properly designed, this integrated pipeline could create more high-expertise teaching for more children in more classrooms more of the time. We have the resources and more than enough dedicated, capable teachers to do this. What we need is committed leadership that is:

- insightful

- humble

- strong

- perseverant

- politically connected

- and thinks in terms of “systems”

I believe our first task is showing policy makers and voters some clear and vivid examples of the complex decision-making and manifold, sophisticated skills that go into good teaching. We have to convince our state legislatures and Congress that teaching is complex work so they scrutinize the way regulations, funding and incentive systems can promote High-Expertise teaching..

Current TV spots and movies often highlight inspiring teachers with charisma. These give deserved visibility to star individuals, but they over-focus on personality characteristics instead of expertise. We don't glorify charismatic medical doctors except in TV dramas; we elevate the perseverance of committed diagnosticians and the skill of successful practitioners. Let's start getting the message across that skillful teaching is as complicated and as consequential to the lives of children as good medical practice.

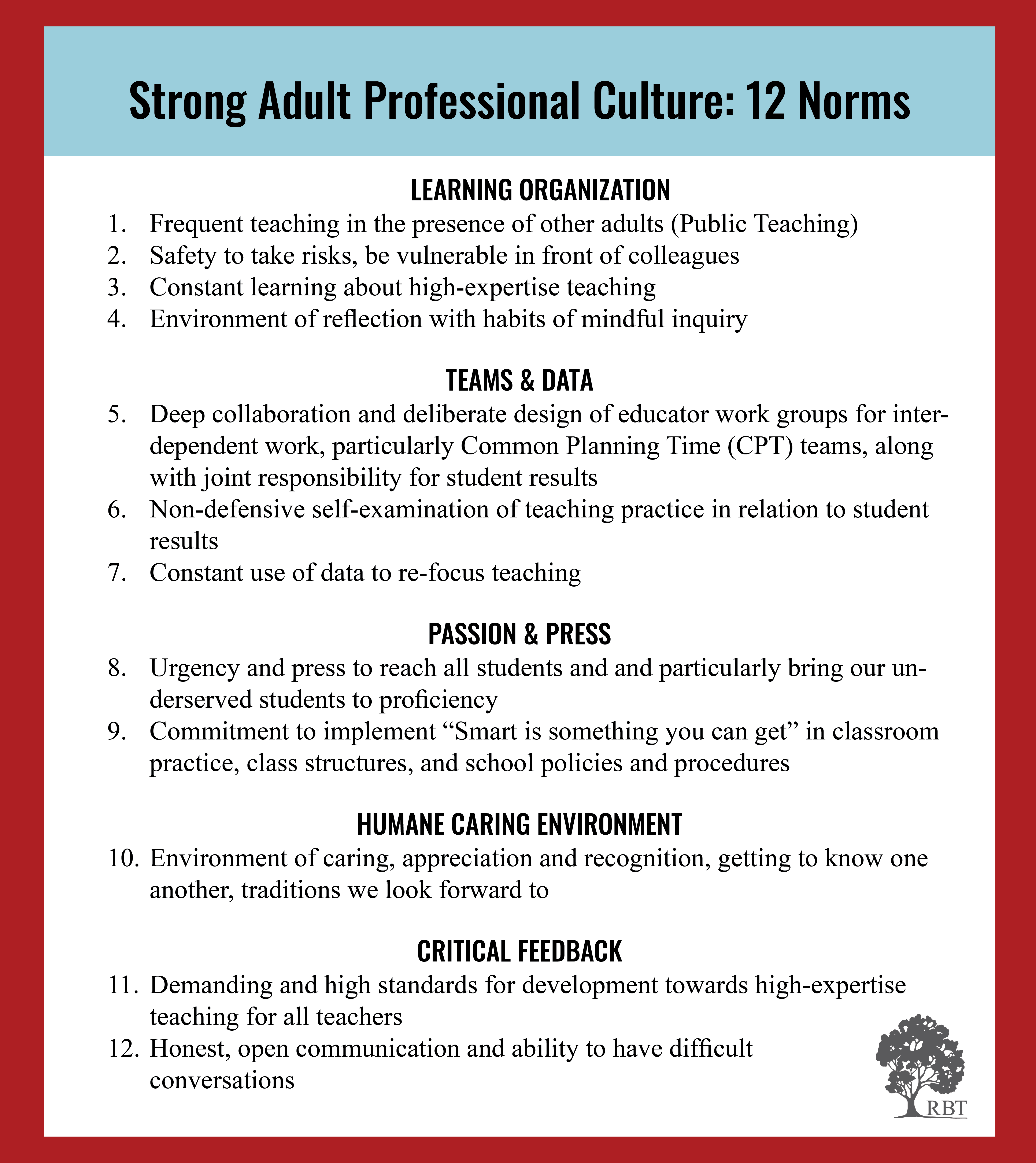

Finally, a word on leadership expertise: there are principals and teacher leaders who create workplaces where constant learning about high-expertise teaching takes place daily in the way business is conducted (Grissom 2021). Many decades of research show that students do better, despite adverse neighborhood and family conditions, if the leaders build strong Adult Professional Culture. The attributes of such cultures are summarized in Figure 2 and discussed in further detail in our Adult Professional Culture Draft Chapter.

Our learning at RBT over 40 years, supported solidly by the research in the references, is that there will be no sustainable improvement in student results and no elimination of the achievement gap until leaders and teachers succeed in making strong the norms of behavior that make for a "learning organization" (Senge 2006).

Many other elements of school practice count, and count heavily (good curriculum; community support; resources; school structures for collaboration like common planning time; and others.) But no matter how well these important areas are structured, they will not accomplish on their own what we need for students unless the adults act as profiled here.

Figure 2

Only leaders can make this so. And it has to be supported and modeled from the top.

“School culture” has many meanings. The meaning we focus on here is the professional working relationships of the adults, not the students, because these professional relationships have a tremendous bearing on what life is like for students. The adult culture is the main shaper of the school’s capacity as an organization to learn and improve its results for students.

While supported conclusively in the literature, skills for building strong Adult Professional Culture are systematically absent from training and certification programs for school leaders. Skillful teaching and skillful leadership are the missing elements of school reform and school improvement.

At the individual district level these are things we can coalesce around now. We can build each school into a reliable engine for the improvement of teaching and learning for equity. This is within the grasp of any district that is willing to think systemically and plan long-term with courage and conviction.

Counties and states are the units of enduring change in American education because they control teacher licensing, certification of teacher education institutions, student testing, and the parameters of funding which can work toward equity or institutionalize the inequality of

local taxation through property taxes. To influence state and county policy makers (county school boards in relationship with county councils, which provide funding allocations) and state legislators on education committees, educators need to get active, to get political, and to gain influence.

In the meantime, every aspect of developing a strong personnel pipeline for expert teaching and expert leadership can be undertaken right now at the district level, and for small district through consortia of districts like New York’s BOCES, Ohio’s ESCs, Oregon’s County Collaboratives and similar structures that exist in each of the 50 states.

Resources

References

Bellon, Jerry J., Elner C. Bellon, MaryAnn Blank. Teaching from a Research Knowledge Base. Merrill. New York: 1992

Bryk, Anthony, Penny Sebring, Elaine Allensworth, Stuart Luppescu, John Q. Easton. Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press. Chicago: 2010

Danielson, Charlotte. Framework for Teaching. ASCD. Alexandria VA: 2013

Fink, Stephen. "School District Leaders as Instructional Experts: What We Are Learning." Center for Educational Leadership. University of Washington School of Education. Feb. 2017

Goodlad, John. A Place Called School. McGraw-Hill. New York: 1984.

Grissom, Jason A., Anna J. Egalite, and Constance A. Lindsay. 2021. “How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research.” New York: The Wallace Foundation. Available at http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis

Hattie, John. Visible Learning for Teachers. Routledge. London: 2012

Hiebert, James and James W. Stigler. "Teaching versus Teachers as a Level for Change: Comparing a Japanese and a U.S. Perspective on Improving Instruction." Educational Researcher. AERA. 46/4, May 2017.

Marshall, Kim. Teacher Evaluation Rubric. Marshallmelo.com. Brookline MA: 2014

Marzano, Robert J. The Art and Science of Teaching, ASCD. Alexandria, VA: 2007

Marzano, Robert. Teacher Evaluation Model. marzanocenter.com. 2015

Mendro, Robert; Bebry, Karen "School Evaluation: A Change in Perspective." Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (New Orleans, LA, April 24-28, 2000)

Nye, B., Konstantopoulos, S. & Hedges, L.V. “How Large Are Teacher Effects?” Educational and Policy Analysis, 26(3), 2004

Pianta, R.C., J. Belsky, R. Houts, F. Morrison, Opportunities to Learn in America’s Elementary Classrooms. Science. 30 March, 2007

Saphier, Jon. John Adams Promise. Research for Better Teaching. Acton: MA 2005

Saphier, Jon. “Another Inconvenient Truth.” Research for Better Teaching. Acton, MA: 2010

Saphier, Jon. High Expectations Teaching. Corwin. Thousand Oaks CA: 2017

Saphier, Jon, MaryAnn Haley-Speca, Robert Gower. The Skillful Teacher. Research for Better Teaching. Acton MA: 2018

Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Random House. New York: 2006

Footnotes

(1) Sixty six percent of all U.S. fourth graders scored "below proficient" on the 2013 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP)

“In the United States, 14 percent of the adult population—a staggering 32 million adults—cannot read.” http://thencbla.org/literacy-resources/statistics/

“What’s more shocking is that we haven’t moved that needle in 10 years. We know that literacy helps people escape the bonds of poverty and live longer. We know that people who are literate are more inclined to vote, take part in their community, and seek medical help for themselves and their families. They’re also better equipped to take advantage of knowledge jobs, which are growing at explosive rates.” – Marcie Craig Post, Executive Director of International Literacy Association, in a panel discussion at the Institute of International Education in New York City, April 2015.

(2) It is irksome that the popular press continues the myth that educators cannot agree on what good teaching is.

(3) The Pianta study (2007) finds only a 1-in-14 chance that a child will have a rich, supportive learning environment. Fifth graders in their sample of 2,500 classrooms in 400 school districts across the United States spend 91% of their time listening to the teacher or working alone, usually on low-level worksheets. 75% of classrooms are “dull bleak places.” These findings mirror those of John Goodlad 25 years ago in A Place Called School (1984). Nothing has changed.