Name It…The Other Epidemic

Covid has shaken our entire education establishment and made 2021-22 the most difficult year in history for American educators as well as for children and their families. Scores of our students have forgotten how to do school, and teacher shortages, weekly Covid tests, and lack of subs make every day a struggle. Hard as it may be to realize in this chaotic year, time will diminish these particular struggles. But COVID has exposed another, more insidious epidemic that is affecting almost every school in the country – a mental health crisis of previously unimagined proportion. Jeff Levin and Judge John Broderick make the case here that this situation needs to be considered deeply now, and they offer solutions. |

Jon Saphier |

A Boston Globe op ed from September 13, 2021 cited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finding that 17 percent of children between the ages of 2 and 8 had a diagnosed mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder. For children living below the federal poverty level, that number rose to 22 percent.

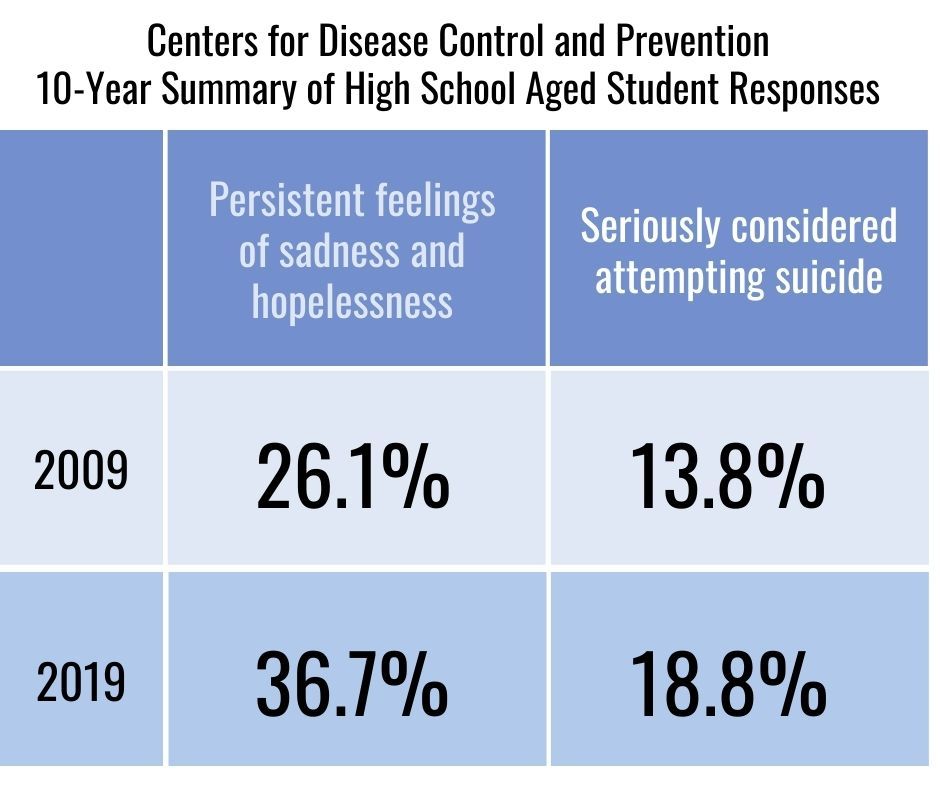

Unlike COVID, the student mental health crisis did not hit us all at once—it’s been coming for 20 years. The rise in teenage suicide and depression in only the last 10 years is stunning. The opening paragraphs of Raising Happy, Confident Children in the Digital, Post-COVID Age paint a tragic and alarming picture. For example, a 10-year summary from the CDC shows a large rise in the percentage of H.S. age students experiencing the following conditions:

- Persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness from 26.1% in 2009 to 36.7% in 2019

- Seriously considered attempting suicide from 13.8% in 2009 to 18.8% in 2019

I have hugged more students with wet eyes and cracking voices in gyms and auditoriums across northern New England these past five years than I ever knew existed. My eyes have been opened. |

Chief Justice John Broderick |

We are going to make the case that the current movement for teaching SEL skills is a necessary but insufficient response to the new scale of the problem. What we can do and must do first is explicitly acknowledge with students the issues causing extreme anxiety and involve families more directly.

When Jeff first started to talk about these new conditions 20 years ago, no one seemed to know what he was talking about. But things have changed. Now after John Broderick’s frequent talks to HS audiences about his own family tragedy with a child experiencing – and concealing – a mental health crisis, the lines of students were often longer than they are for Santa with children who wanted to share their story and get a hug from a complete stranger. As John says, “I have hugged more students with wet eyes and cracking voices in gyms and auditoriums across northern New England these past five years than I ever knew existed. My eyes have been opened.”

There is a standardized measure for student mental and emotional health; thousands of school systems have used the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavioral Survey for decades. The data confirm what we are seeing. However, schools are not usually assessed based on this survey, and many school systems don’t share the often disturbing results with their communities. That can contribute to the lack of awareness of this issue.

In our experience, school administrators and teachers are aware of the student mental/emotional health epidemic, but it is rarely discussed because of the stigma that still surrounds these issues, the worry that schools are going to be blamed for the problem if they bring it up, and, most importantly, the apparent lack of broad solutions.

Having said that, no one is trying harder than educators to fix the problem. The big push for teaching SEL is one important approach. However, we must examine the root causes, because trying to change a behavior without identifying and addressing the root cause is often ineffective. We have found when looking at these problems from 10,000 feet, many behavioral issues are related. The same dynamics that are causing the student anxiety epidemic are also causing the vaping epidemic… and the suicide epidemic… and the phone/social media addiction epidemic… the sexting epidemic… and the failure-to-launch epidemic where young people, often into their 20s and 30s, are sitting in their parents’ basements playing video games all day.

It’s like an iceberg: All of the behaviors listed above are the visible part above the waterline. But the bigger part, the part under the water, is the enormous stress and anxiety caused by our rapidly changing culture that is driving all of these behaviors and more.

This student mental health crisis is no one’s fault. Again, it’s a cultural problem, and it has come on us so fast, no one was prepared for it. These cultural circumstances affect children directly, but also cause parents to parent differently, which often includes an adversarial relationship with the school.

Because of these cultural changes, there are emotional skills previous generations (we!) learned by osmosis that today’s children aren’t learning. Many parents are afraid to let their children out of their literal or virtual sight, so children’s independence has suffered. Everyone feels financially stressed, whether it is real or just perceived, and many children are pushed in school because college scholarships are necessary in order for college to be in reach, even for relatively affluent families. We have an entire generation of stressed and anxious kids, and adults are stressed, too. Naturally, this seems overwhelming and unfixable.

Thankfully, however, kids are hard-wired the same way they’ve always been. Some may think: " So all we have to do is develop communication and empathy skills with adults and the kids will get better." It sounds simple—but if only it were easy!

As we said, schools didn’t cause this problem. But the school is the only institution that can jumpstart the fix. The SEL movement already tries to address some of the emotional skills deficits in terms of behavior. But unless we first acknowledge the causes of the problem explicitly—to ourselves, and, more importantly, to students—and involve the parents, the SEL movement will not make the needed difference. And many children will continue to be so anxious they are unable to learn.

This isn’t an educational problem. It’s a cultural, community-wide, psychological challenge.

When Justice Broderick and I come into a school, we watch the already overworked staff’s eyes roll because they see another program with initials, another curriculum they somehow have to cram in with all the other curricula they are required to teach, and feel like it’s going to be more work without a guarantee of results.

But “another program” is not how we think the problem should be approached. An example is the Reconnection Project. It has a set of experiences for educating teachers and parents that can make an enormous difference in the lives of all three constituencies- educators, parents, and students. However, there are also important small things, which require minimal training, that schools can do that can quickly give relief to students.

Most importantly for the students, and what we teach, is there has to be a paradigm shift—a cultural shift, if you will—around what we are already doing. It’s not so much additional work as it is a change in perspective.

The Critical Importance of Acknowledgement

One of the first things we can do with our entire school community is NAME THE PROBLEM. Our children of all ages are witnessing, on their phones if not in person, what seems to be a world falling apart. Climate change is causing our country to either burn up or wash away. Shootings are happening in places that used to be 100% safe, including and especially schools. People are being killed right on camera, either by terrorists or by the people who have sworn to keep us all safe. Gridlock, fighting, and denial are seen at every level of government. The world seems crazy, yet the adults in childrens’ lives for the most part never talk about it. They just go about their lives as if nothing is wrong. Consider how stressful that is for children!

We call this list of things the Overwhelming Tragedy List and refer to them as The Elephants in the Room. And we posit that if we adults would just acknowledge them, a lot of kids will feel a lot better. Because you better believe that the kids want—NEED—to discuss these things.

As an example, here are the comments after one acknowledge-the-problem session we did in a N.H. high school:

- They appreciated that even though you’re older than they are, you didn’t judge their generation.

- They want/need more time to discuss these elephants.

- They liked how people chose to open up yesterday.

- They want you to come back!

- They want to open up more about their baggage.

- They want to discuss how to silence the little gremlins [from Rick Carson’s excellent book, Taming Your Gremlin].

- They want to figure out how to talk about their elephants outside of this class.

This is after one session. This kind of discussion can be done without days of training (although some training is needed) for teachers. It’s not implementing a year-long curriculum. And it can be done immediately.

There are other things that can be done, such as orienting existing classroom activities to develop what we call the Six I’s—identity and the building blocks of identity which are imagination, independence, integrity, intimacy, and intestinal fortitude. Doing this kind of work gives students confidence and connection, which often make them feel less anxious.

Involving the Parent Community

Being a kid—or a parent—has always been hard, but now it is harder. Students are in school only six or seven hours a day—and now, with the pandemic, some days they might not actually be in school at all. We need to change how things feel for students, but we cannot do so without parents. There are now many parents whose niggling feelings that something was not quite right with their kids were confirmed after observing their children during the COVID epidemic and watching them struggle now as we’re trying to come out of it. In our experience, many parents feel overwhelmed and want to be given the skills to help their children—they, too, are waiting for guidance. No matter how we communicate with them, we have to meet them where they are. And that means giving them concrete, proactive suggestions on how to parent in the Digital Age. That will help many of them, and they will be grateful. Here are just a few topics that can be developed with parents, but there are many more:

- Develop a felt sense of the granular difference between our childhoods and the students’.

- Find a balance between preparing children for adulthood and protecting them from harm.

- Eliminate outcome fever: change focus from what children do to who they are.

- Use new techniques to respond to a child’s struggles without “rescuing” or enabling.

We have found that today’s students are smarter, more open, less judgmental, and more informed than any prior generation of Americans. But they have not grown up in an “eyeball to eyeball” world where social/emotional growth seemed easier to acquire. Rather, they spend inordinate amounts of time wandering alone in a virtual world where social/emotional growth is in short supply and where the lines between night and day and school and home have blurred. Their lives are too stressed, too time-pressured, too scheduled, too over-organized, too competitive, and too outcome-focused to allow for the luxury of a less harried natural growth and development.

We have in many ways shortened childhood to the detriment of the intangible benefits of a more natural and less impatient journey to self-discovery. Today’s parents, too, have less time and more daily stress than in years past. In combination, these forces have unwittingly burdened today’s kids and short changed their emotional growth and resilience. Something needs to change. Acknowledging current realities is a vital first step. We need a new, nonjudgmental conversation and the courage and wisdom to make real adjustments. Change is both possible and essential. We have hugged too many hurting kids to believe otherwise.

About the Authors

John Broderick was Chief Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court. Now, as Senior Director of External Affairs for Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health, Justice Broderick has spoken to almost 90,000 middle- and high-school students at 300 schools about his own family’s journey. Broderick can be reached at Dartmouth-Hitchcock at johntbroderickjr@gmail.comor (603) 496-3378.

Jeff Levin is a life coach who has worked with individual young people, families, teams, and schools for 40 years. He can be reached at jeff@jefflevincoaching.com, (603) 496-0305, or https://www.jefflevincoaching.com.

Justice Broderick and Jeff often work together to help school leaders address and solve the new mental health challenges that we’re all facing.

References

Levin, M.K., and Levin, Jeffrey N. Raising Happy, Confident Children in the Digital, Post-COVID Age: The Cultural Causes of the Anxiety Crisis in Children and What We Adults Can Do to Help Them. 2021. https://www.jefflevincoaching.com/raising-children-in-the-digital-age