The Teacher Opportunity Gap

May, 2021

There is a terrible cost to our students that teachers work without the conditions of a true profession around them. Legions of teachers operate at a highly professional level anyway, despite the odds, but the majority are denied the professional pathway that would give them the expertise they need and want. And it is our children who suffer, especially those marginalized by poverty and racism.

The knowledge and skill for high expertise teaching is:

- Far larger and more complex than acknowledged by our policy makers and our systems of professional learning

- Crucial for marginalized students who could meet proficiency if they had expert teaching

- Significantly absent from most teachers’ opportunity to learn

The “opportunity gap” has appropriately replaced the “achievement gap” as a term to describe the difference in academic achievement between white children and children of color. The point of the phrase is that our education system denies children of color the same opportunities to learn as their white peers, so don’t blame the children. There’s nothing wrong with them. It’s adult decisions and policies that have created what is called the “ gap.” It is the same with teachers and the “expertise gap.”

The defining attribute of a profession is expertise that is commonly acknowledged and codified. It has a common language and concept system that goes with it. (Saphier 1994). There is a clear career path that allows, nay requires, that practitioners enter the workforce with competent novice capacity, and then continue to learn through structures and experiences through which they must travel.

In this piece I'd like to add a layer of content and urgency to the argument so many have urged over the last 40 years (Art Wise, Linda Darling-Hammond, John Bransford, Deborah Ball, Richard Elmore, etc...) about creating a true profession of teaching (and leading).

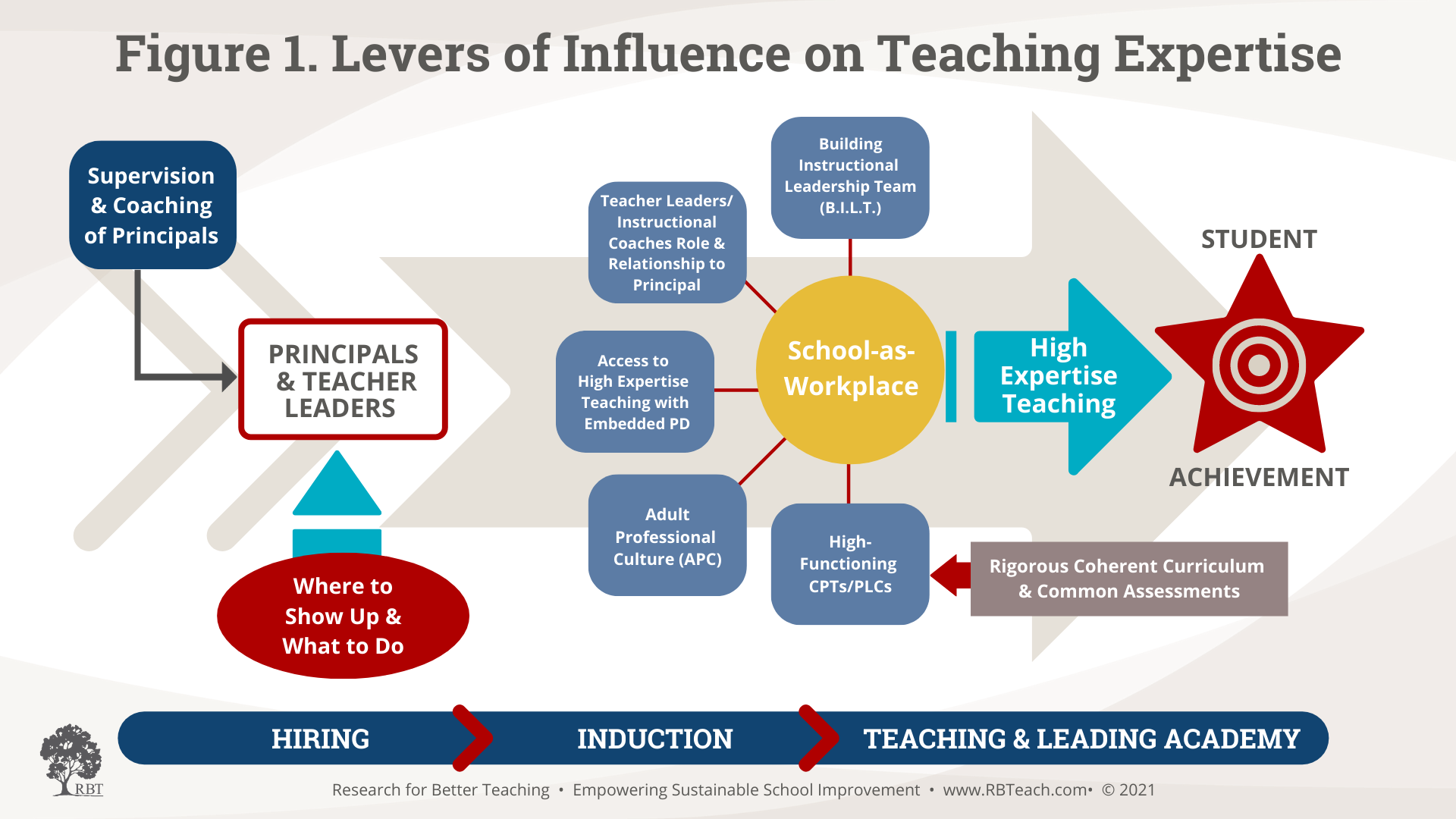

First, we can name the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that comprise high-expertise teaching across its full range, describe them in detail, and show what they look like and sound like in action. We can do this now and with agreement across the field. Second, we can identify the main levers of influence on teaching expertise, the processes that could influence teacher knowledge and skill, most of which are internal to school districts and shown in Figure 1. We can redesign them so they systematically contribute to individual teacher’s expertise – consistently, and powerfully aligned with the needs of individual teachers and their students. Finally, we can align these processes and make them operate from an ethos of both support and of accountability. Figure 1 names these processes.

There are other mechanisms that provide important support to an aligned system for developing high-expertise teaching, such as rigorous curriculum, but they are much less potent if not grounded in the expertise of the people who use them.

It is important to underline that expertise in any profession is not about implementing singular “best practices”. It consists of making informed judgments about what to pick from one’s repertoire; best-estimate choices, conditioned by the wisdom of experience and knowledge of students. (Saphier 1979, Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. 1993; Cohen and Ball 1995; Shulman 2004 ). The repertoires are all the accumulated options for handling a particular task (such as unscrambling confusion, illustrating a concept, building a relationship, designing a culturally relevant lesson, getting discouraged students to believe in themselves, and on and on).

Coda: the significance of school leaders (Grissom 2021) and the associated calls for better preparation and certification of leaders is right on target. The prime reason is that successful leaders create the urgency and the school conditions for deep collaboration and constant learning by their faculty – creating a “learning organization” as Senge christened it (Senge 1990). All faculty members are constantly acquiring bigger repertoires for handling the tasks they encounter each day and collaborating to make the right choices as they problem-solve with colleagues in teams. That’s exactly what true professionals do, and what the best scientists and clinicians do in any field daily.

Figure 1 displays the prime mechanisms to re-engineer so they focus on professional learning about teaching expertise. They can be aligned with one another to drive constant teacher learning about high-expertise teaching. A district that takes this argument to heart could begin this re-engineering work right now and make the reentry of children and adults to school in 2021-22 more than “getting back to normal.” With the additional federal funding available for a short two years, we have an unprecedented chance to aim for better than “normal” and put teaching and leading expertise at the center.

References

- Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: An inquiry into the nature and implications of expertise. Open Court Publishing Press.

- Cohen, David K and Deborah Lowenberg Ball. (1999) “Instruction, Capacity and Improvement.” CPRE Report Series RR-43. University of Pennsylvania .

- Darling-Hammond, Linda and Bransford, John. (2015) Preparing Teachers for a Changing World. John Wiley.

- Elmore, Richard. “Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice.” Harvard Educational Review, Spring 1996.

- Grissom, Jason A., Anna J. Egalite, and Constance A. Lindsay. (2021). “How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research.” New York: The Wallace Foundation. Available at http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis.

- Saphier, Jon. (1979) The. Parameters of Teaching. Boston University.

- Saphier, Jon. (1994) “Bonfires and Magic Bullets.” Research for Better Teaching.

- Senge, Peter. (1990) The Fifth Discipline. Doubleday.

- Shulman, Lee. S. (2004). The wisdom of practice. Jossey-Bass.

- Wise, Arthur. E. (2019). “Toward equality of educational opportunity: What’s most promising?” Phi Delta Kappan, 100(8), 8-13.