Starting the Year with Clarity and Conviction about Expected Behavior

Do we (teachers) have clarity about what behavior we want from our students? Do we have conviction about what we can reasonably expect from them? The distinction here is an important one:

- clarity about what we want a student to do or measure up to is about setting standards of behavior

- what we think a student will do—or is capable of doing—is about our beliefs and expectations.

Each plays a critical role in the results we get from students. If we aren’t clear about standards of performance, students won’t know what we’re asking of them. If we don’t have conviction that students are capable of achieving a standard of performance, we aren’t likely to inspire them to do so.

If we aren’t clear about standards of performance, students won’t know what we’re asking of them. If we don’t have conviction that students are capable of achieving a standard of performance, we aren’t likely to inspire them to do so. |

Is it reasonable to expect first graders to sit and listen at a classroom meeting for more than 15 minutes? Are they capable of doing so? If you believe that your first graders will never be able to sit for more than 10 minutes, they won’t. Are your secondary students too conditioned to interrupting to give respectful silence to peers during a mock debate? If we believe that, then disrespect is what we will observe.

Every year, we at Research for Better Teaching work with at least one or two excellent teachers who are talented and caring people, but whose effectiveness is reduced by their ambivalence about expectations. They are unsure how reasonable it is for them to expect more responsible and attentive behavior in class and to push students toward that behavior. They see the irresponsible behavior of students who appear out of control but have family and other problems, and feel they must make allowances. They thus undersell the children and undershoot with their goals for student behavior. Who says first graders can’t sit still in a circle and listen to one another for a 15-minute meeting? Who says ninth graders can’t learn to function in self-organized task groups to plan and organize a project?

Again and again, we have seen it demonstrated that teachers can get the behavior they want if they work hard enough at it, are tenacious and determined enough, are committed to the idea that it is right and attainable behavior for their students, and are willing to teach the skills their students may need to function at that level. |

Again and again, we have seen it demonstrated that teachers can get the behavior they want if they work hard enough at it, are tenacious and determined enough, are committed to the idea that it is right and attainable behavior for their students, and are willing to teach the skills their students may need to function at that level. This is true even for some of our most challenging students. It just might mean defining and teaching the skills at a different level of nuance, adjusting our approach, and, it most certainly will take longer to achieve the goal, but achieve it they will. Expecting anything less, or allowing ourselves to believe that not all will achieve,is ultimately a disservice to students. What we decide to “want,” or the standard we set, of course, can be unreasonable and age inappropriate, in which case what we get is what we deserve.

If you have a clear notion of what you want, and keep expecting, expecting, expecting, and say so out loud to students, with consequences when they don’t measure up, with explanations of “why” over and over again, and with as much kindness and rationality as you can muster, you will get there. But first you must make some decisions about what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior, prioritize what behaviors you want, and decide that you will commit to getting them.

If you have a clear notion of what you want, and keep expecting, expecting, expecting, and say so out loud to students, with consequences when they don’t measure up, with explanations of “why” over and over again, and with as much kindness and rationality as you can muster, you will get there. |

The Taboo Exercise

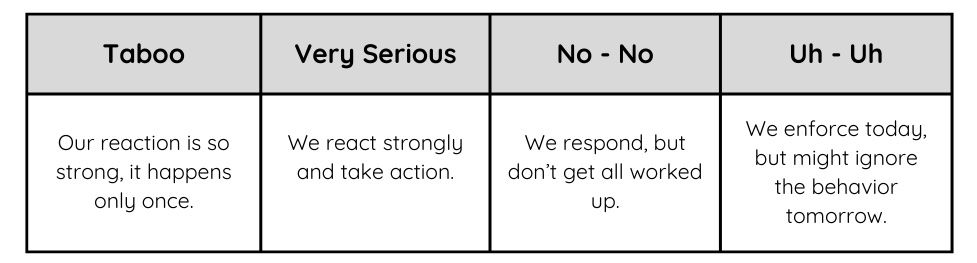

The Taboo exercise is a useful first exercise for faculties to do together to gain clarity, consensus, and conviction about behavioral expectations. Through the exercise, and the discussion it necessitates, participants draw distinctions between, on the one hand, the most serious and unacceptable student behaviors that warrant uniform, immediate, and consistent responses and consequences from the whole staff and, on the other, behaviors that are important to address or extinguish, but far less serious and therefore not worthy of community time and investment. In the latter case, individuals decide how to address the infractions. The exercise begins with participants privately and silently brainstorming behaviors they are bothered by and want to minimize or eliminate. They record each behavior on a single sticky note. After brainstorming, they spend at least five minutes sorting each behavior, according to their own standards, into one of four categories on their own chart:

- Taboo—the most serious of behaviors. A student should do this only once because the reaction will be strong and total.

- Very serious—behaviors that are important to respond to, with swift and strong consequences. These are behaviors that would seriously threaten the social order and the climate if they were allowed, but they are not quite as serious as the taboos.

- No-no—behaviors that are against the rules and are responded to every time, but they are not a cataclysmic event. There are consequences, but the level of response is measured in comparison to the first two behaviors.

- Uh-uh—behaviors students shouldn’t do and for which there are rules, such as raising hands to speak in class, but enforcement may vary with conditions and mood.

Next, in small groups, teachers share what they have in each column and explain their reasons. Their task is to come up with a consensus chart. The resulting discussions are animated, informative, and productive. You can make something a taboo only if you have the power to do so with some social capital in the community to back you up. For example, many would like to make fist fighting a taboo anywhere on school grounds. In certain communities, however, because of the peer and adult culture, we do not have the power to make fighting a once-only occurrence. Therefore, fighting may be relegated to the Very Serious category. People change their opinions, both up and down, about the significance of certain behaviors when they hear the rationale of others. A sixth grader climbing the chain-link fence in the recess courtyard moves up in Jim’s mind to serious when he hears Clarisse’s point about how dangerous a fall could be, especially with the occasional glass on the tarmac. Cursing moves down from a taboo in Marcia’s estimation, although it is still extremely offensive to her, because she realizes how prevalent and almost colloquial it is in the student culture. She succeeds, however, in elevating cursing to a no-no behavior for Jim and Clarisse because she convinces them how important respectful language is to a focused academic environment.

People change their opinions, both up and down, about the significance of certain behaviors when they hear the rationale of others. A sixth grader climbing the chain-link fence in the recess courtyard moves up in Jim’s mind to serious when he hears Clarisse’s point about how dangerous a fall could be, especially with the occasional glass on the tarmac. Cursing moves down from a taboo in Marcia’s estimation, although it is still extremely offensive to her, because she realizes how prevalent and almost colloquial it is in the student culture. She succeeds, however, in elevating cursing to a no-no behavior for Jim and Clarisse because she convinces them how important respectful language is to a focused academic environment.

These discussions lay a foundation for consistent faculty responses to student behavior and for determining what the consequences will be when a student violates them. They are particularly important in secondary schools, where students may experience wide inconsistency in adult standards across the five or more teachers they see daily.

These discussions lay a foundation for consistent faculty responses to student behavior and for determining what the consequences will be when a student violates them. |

Do Students Know What Behavior Is Expected of Them?

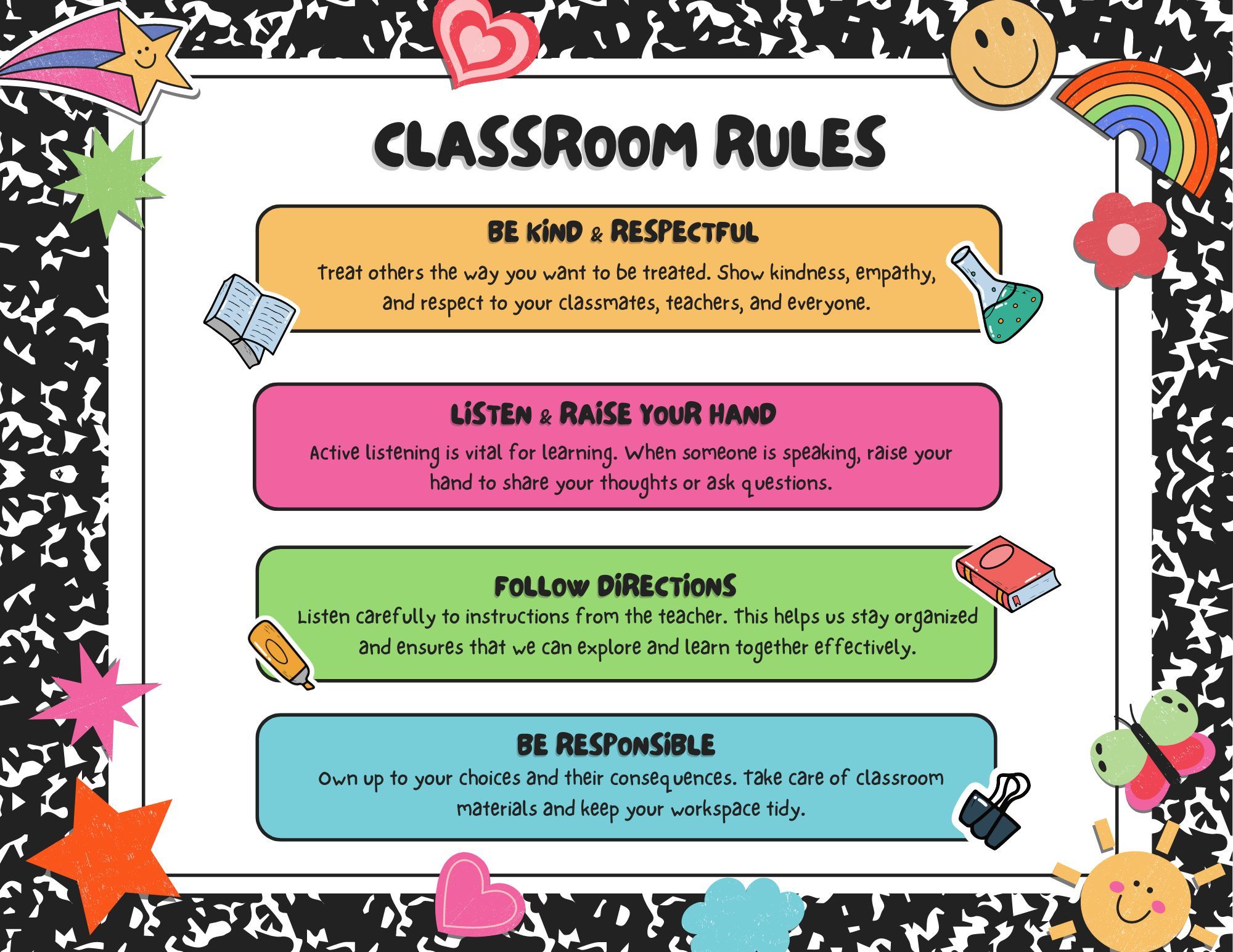

The prerequisite for strength in this area is that students have a clear and unambiguous picture of the expectations for their behavior. Something must happen to get that information across. There are numerous ways this may be done: tell them directly, make up a chart, brainstorm, or negotiate the class rules at a class meeting. Expectations are sometimes not codified as formal rules or laid out all at once, but they become known to students through what a teacher reacts to consistently. However it happens, students must be clear about what we want from them, and we save a lot of time and energy if we communicate expectations directly rather than leaving it to chance that students will figure them out.

However it happens, students must be clear about what we want from them, and we save a lot of time and energy if we communicate expectations directly rather than leaving it to chance that students will figure them out. |

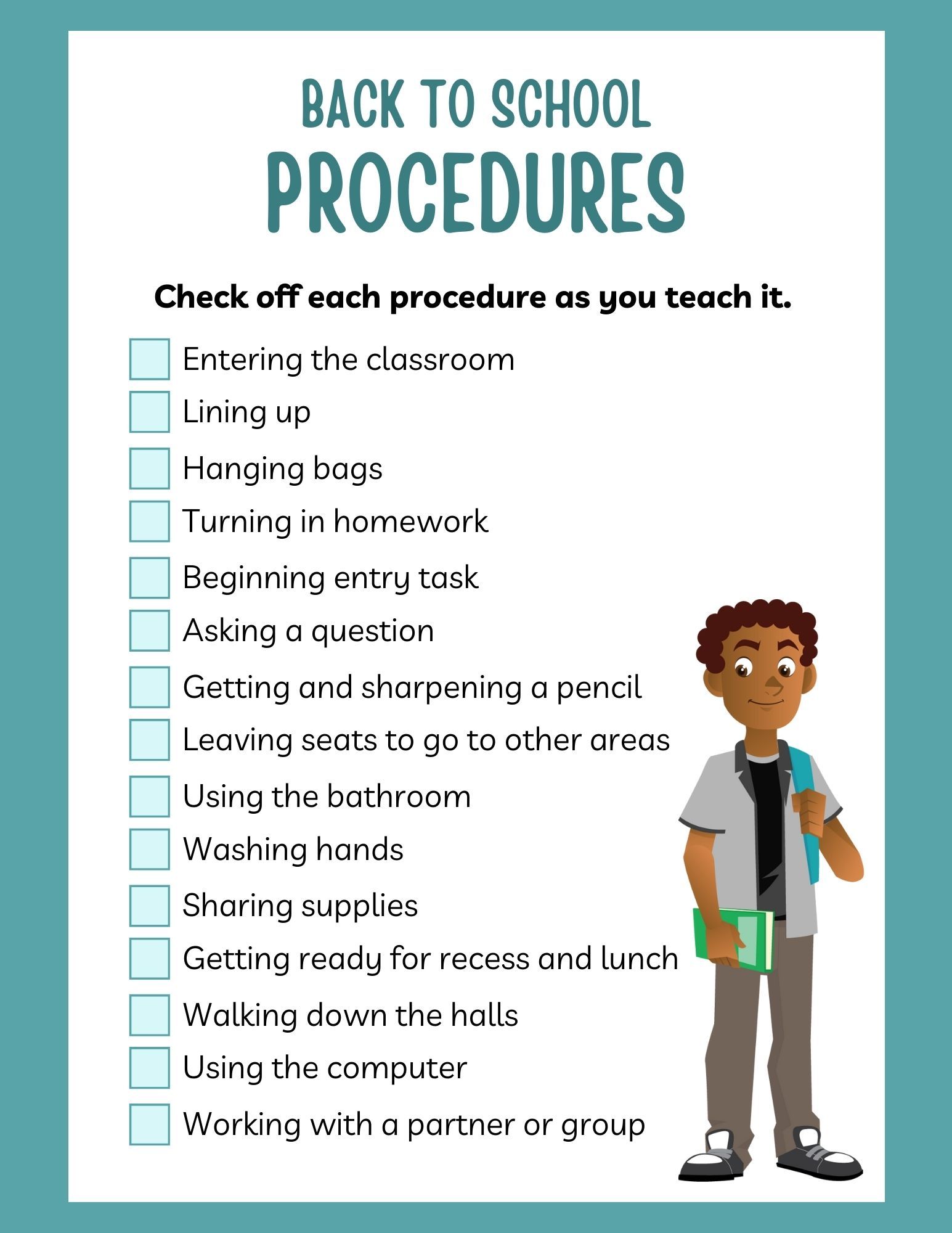

The opening weeks of a term or year are the prime time to ensure solid understanding of behavioral expectations, to establish routines, and to begin to build class cohesion. It is useful to think of this period at the beginning of the year as one of teaching or training for the students. Training requires practice; thus, if students are noisy and disruptive in the hallway, the teacher can say, “I can see we need more practice in hall-walking from the way we just came back from gym,” and take the class out for some practice right then. This is not punitive; it is logical as a consequence.

Example. Nick Aversa, an eighth-grade teacher we worked with, spent the first part of every period in the first weeks of school rehearsing his students in how to enter class and get right to work. The routine included crossing the threshold to class and stopping all talking, finding a seat, getting out their notebook, and working on the opening activity for class. Initially, he taught them why this is important and then walked them through a series of practices from hall to classroom. From then on, anytime someone forgot the procedure, the consequence was to go back out into the hall and reenter correctly. Nick would signal this by simply establishing eye contact with the offending student and then looking at the door. The student would know what they had to do.

We have seen classes where the teacher’s expectations for student behavior are lowered by the students; their behavior is so poor that the teacher concludes they can’t behave any better. Watch out, though; the minute a person starts justifying behavior (or academic achievement, for that matter) by saying, “What can you expect, given their environment?” the students are in trouble. We at RBT are convinced that what you expect is what you get—not right away, of course, but eventually. The students may have to be taught how to meet higher behavioral standards, but they are not constitutionally, genetically, or environmentally unable to.

There are examples all over the country which demonstrate that children from the most chaotic and disadvantaged families and neighborhoods can behave perfectly well in school if the adults demand it, teach them how to do it, and believe in them. |

There are examples all over the country which demonstrate that children from the most chaotic and disadvantaged families and neighborhoods can behave perfectly well in school if the adults demand it, teach them how to do it, and believe in them. This last factor, “believe in them,” is the subject of a large part of our professional development work with teachers and school leaders, as well as the subject of an entire section of The Skillful Teacher and addressed in finer detail in our book, High Expectations Teaching. Students who don’t believe school has any value for their future, especially in secondary grades, are much more likely to be discipline problems; they feel they have little to lose. Maybe they are frustrated and angry. Building their motivation to succeed in school therefore has a strong bearing on their willingness to respond to the environment of responsibility and self-discipline that this chapter discusses. Our point here is simply to alert readers to our responsibility, both in our individual classes and collectively for the school, to maintain the highest standard of civil and respectful behavior for our students.

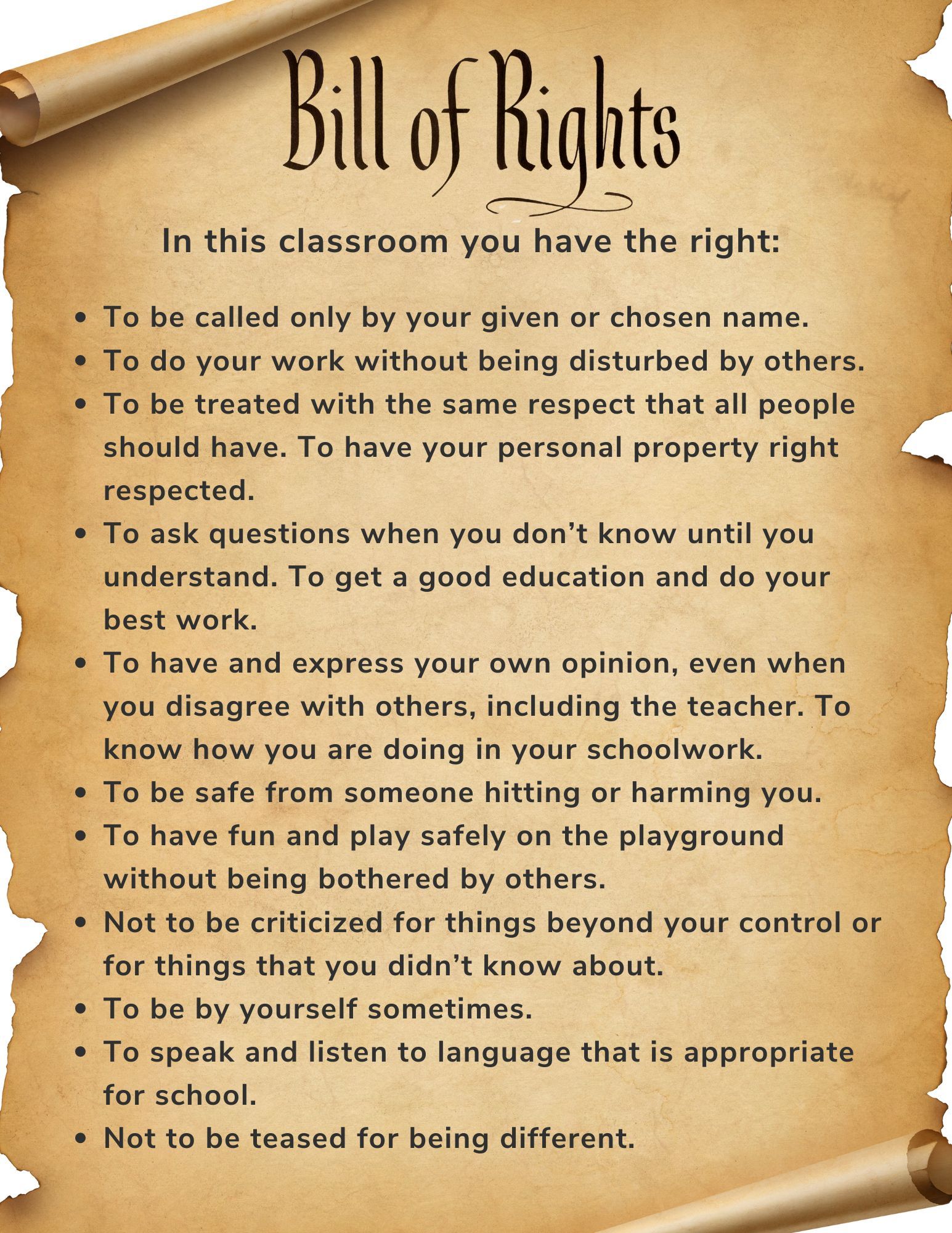

Some teachers call this beginning-of-the-year rules exercise constructing a “classroom constitution” or “bill of rights and responsibilities.” A colleague of ours and a former classroom teacher, Dave Crump, used to start each school year by having his students develop a list of what they wanted to be able to count on as rights to be respected in their classroom that year. Once they had generated a good list, they would discuss what each idea meant and why it was important. Finally, they would vote on their top priorities and construct a manageable list of 10–15 rights that all promised to abide by. The final document was prepared, and each student signed it. When infractions occurred or conflicts arose around behavior, Crump would send students straight to the bill of rights to determine which of their rights had been violated—or which right they had violated—and to decide what a fair consequence might be. Frequently this deliberation and discussion diffused tension between peers, and by the time they were reporting back to Crump, they had pretty well resolved their issue.

Sample Bill of Rights

Source: Reprinted courtesy of David Crump, principal, Harrington School, Lexington, MA.

How you expect all students to behave needs to be repeated often. That means, especially in the beginning of the year, restating and reminding students about expectations and eliciting expectations from students just prior to events that may strain the behavior—for instance: “We’re going to the auditorium now. What might it be like there as we walk in? What will we need to do? What should we keep in mind for our behavior as a good audience?

Connecting with Home

Another useful strategy to clarify and reinforce expectations and build relationships with families is early home contact with parents to establish a positive connection long before problems arise and to enlist their support and cooperation throughout the year in reinforcing the class contract The key here is to connect before problems arise so that if and when they do, you have already have an established rapport.

In an older book Jones (1987) offers the following excellent guidelines for early contact with parents of elementary school children:

Send home a welcoming letter to parents and students and attach a copy of the general rules for the class. Call every parent sometime during the first few weeks of school. Make five calls each night—5 minutes long—so the job isn’t burdensome:

- Introduce yourself.

- Briefly describe the highlights of your curriculum.

- Say something positive about the child—good news only. (If there is already bad news, save it for another day.)

- Discuss the classroom standards that you sent home. Answer any questions they might have about them. Ask for their support in conveying to their children the seriousness of the rules and structures of school.

- Ask about any special needs of the child: medical conditions you should know about? academic concerns they might have?

- Tell the parents that you need their help through the year. Acknowledge that they sometimes hear about a concern or issue before you will and request that they contact you if it is worrisome. State that in turn you would like to feel free to contact them if you hear about something worrisome. Underscore your desire to work together so that bumps in the road can be ironed out before they become “real problems.”

- Conclude by inviting them to “Back to School Night.”

- Consider a follow-up call randomly to one parent a week. (pp. 155–156)

Here are Jones’s guidelines for parents of children in secondary school:

- Make a welcoming phone call [as described for children in elementary school] to the parents of the 5 students in each of your classes whose misbehavior is likely to produce a parent conference before long.

- Intermittent calls. Pull the names of 2 students per class period per week. Call the parents over the weekend. Strengths and assets of the student will be the focus, but problems will also be discussed. It is amazing how an on-going, random, spot check system of feedback to parents can both put students on their toes regarding the following of classroom rules and generate good will from students and their parents. Literally anything personal says you care.

- Send a form letter home conveying the same information that might be conveyed over the phone. (p. 134)

So, as you prepare to start a new school year, be sure you take time to get clear on your standards for behavior, and take time to examine each one to ensure that you are clear about exactly what it looks like to meet those standards, how you are going to communicate and demonstrate these standards to students at the beginning of the year and how they’ll stay top of mind for teacher, students, and parents as the year progresses.

But remember, that just as important as being clear about the standards, is grounding them in the unwavering belief or expectation that each and every one of your students will be able to meet the standards given time and persistence - and this message is integral and essential every time you introduce, revise, or revisit the standards you set for behavior in your classrooms.

Check out our other blogs

Topics to help you plan for the school year ahead and to keep you going throughout the year.